I’m reading this on the 758 Greenline bus from Hemel Hempstead to London. This would be inconsequential except for the fact that I’m reading about the young Tony Judt riding the Greenline buses to school. He describes the difference between them and the normal red buses and how, because they served the outer areas, they were slightly more middle class, and how class differences were still quite marked in the 50s. Their routes crossed London from one side to another, with limited stops so they were like long distance coaches and so they had a little extra glamour. I can remember those buses from my childhood and how they felt, in some strange way a little more exotic than the normal double decker. Any romance is long gone and all that remains is a service, now run by Arriva, which merely retains the name. There are a few routes from outlying towns into Victoria and I’m lucky that one serves my town. I can get into London easily but don’t really think much more about it. Nevertheless it is an immediate connection with what I am reading but not the only one. I’m only a few years younger than the author and share his sense of the times, even if our life experiences are different.

This is a strange little book, written near the end of Tony Judt’s life, full of discrete memories, each 8-10 pages in length. (Feuilletons he calls them - I had to look the word up. Apparently it comes from the section in French political papers set aside for lighter articles of gossip or reviews). Physically small it feels bigger in the mind because I frequently pause and relate what I have read to what I might know.

The circumstances of its writing make it heroic. He was reaching the end stages of a degenerative disease, ALS, which had rendered him quadriplegic. He described the progress of first losing the physical ability to write, then the voice and then being condemned to long hours of silent immobility - but with a clear mind. For someone, whose life had been built on the ability to communicate, I cannot begin to understand the frustration and despair. Yet his life up to that point had stocked his mind full and this book is the result of sifting through that store, through the sleepless nights. He ends the introductory chapter by saying he is grateful that his life had left him with such a rich seam to mine and that despite the illness he still considered himself lucky. “It might be thought the height of poor taste to ascribe good fortune to a healthy man with a young family struck down at the age of sixty by an incurable degenerative disorder from which he must shortly die. But there is more than one sort of luck.”

It is here I pause and wonder how I would cope with such incapacity. I find it hard to imagine how I would cope with being so trapped, so incapacitated. So here I am just a few pages into the book and in the space of a few, economical words, stumped and staring into space, trying to think how I would maintain a sense of self and what I would value. As I said earlier my progress through the book is frequently interrupted.

I am not yet beyond the introductory chapter. Take this about feelings of frustration with unproductive nights:

“ To be sure, you can say to yourself, come now: you should be proud of the fact that you have kept your sanity - where is it written that you should be productive as well? And yet I feel a certain guilt at having submitted to fate so readily. Who could do better in the circumstances? The answer, of course, is a “better me” and it is surprising how often we ask that we be better versions of our present self - in the full knowledge of just how difficult it was getting this far.”

He transferred these feelings into a character: the alm-uncle, who glowers from beneath furrowed brow and is not a happy man. A perennially dissatisfied alter-ego, who “sits there smoking a Gitanes, cradling a glass of whisky, turning the pages of a newspaper” “Damn” I thought “apart from the smoking that’s me pretty much nailed down”. I think I need to take stock.

And that is what this book is about: taking stock. What I like best about it is that it is sticky, like burrs that attach to you clothing during a country walk.

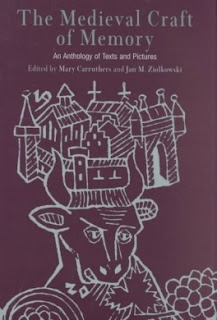

P.S. The idea of a memory chalet follows the mnemonic technique of early ages where events could not easily be recorded on paper. He mentions the work of Frances Yeats and Jonathan Spence describing how people from medieval times would create memory palaces whereby thoughts and images were placed in different places in the envisioned rooms so that the person could close their eyes and walk through their story. Judt did not choose a palace, instead he fixed upon a particular chalet, a small pensione, in the village of Chesières, Switzerland, home to some fond childhood memories. As he explains “In order for the memory palace to work as a storehouse of infinitely reorganised and regrouped recollections, it needs to be a building of extraordinary appeal.”

I have heard of this technique before but have never tried to use it. Instinctively it feels a difficult skill to master but Judt sees it as the easiest of devices, almost too mechanical. Perhaps I need to find out more.

Link to the last bookBoth CLR James and Tony Judt are famous scholars who have written semi-memoirs. James organised his around cricket, particularly West Indian cricket but a lot of it is about his own story. Judt has no great organising theme (apart from his chalet) but to my mind there is a link.

Publication date2010